ABOUT THE COMPOSERS AND THEIR WORKS

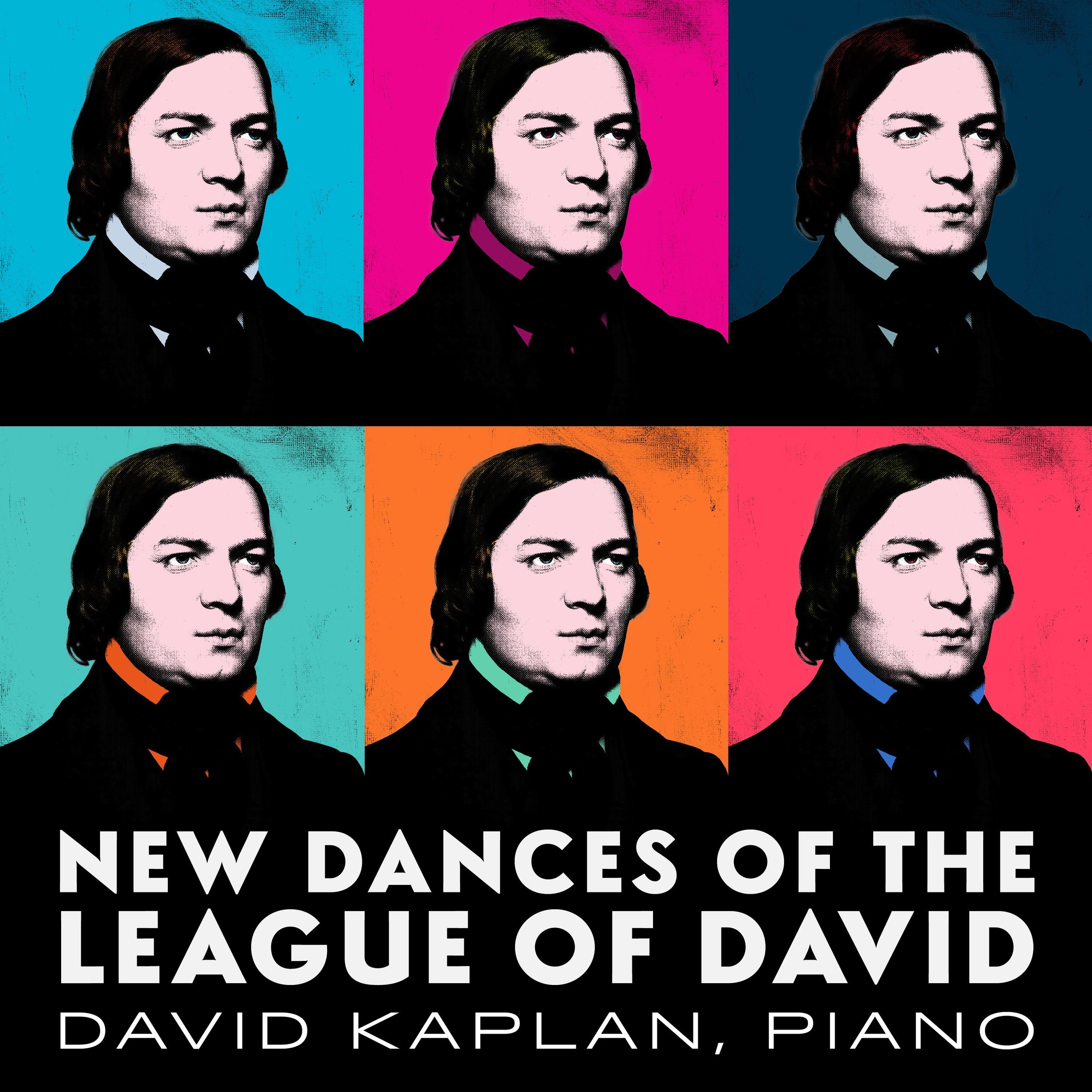

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) – Zwickau, Saxony)

One of the pioneers of German Romanticism, Schumann’s music redefined the parameters of meaning, expression and sound. His piano writing was uniquely innovative and poetic; it stemmed from his early days as an aspiring virtuoso, but even more so from his special relationship with Clara Wieck, one of the greatest pianist-composers of the century, who also became his wife and principal advocate. Much has been written about Schumann’s lifelong struggle with mental illness, which manifests in his music in fascinating ways, including in the proliferation of characters and identities, which often represent his multiple personalities. Though his music earned its place in the canon after his death, Schumann was renowned perhaps more as a writer about music than as a composer himself. His Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, which he published beginning in 1834, served as the principal mouthpiece for his criticism and worldview, as well as for the dramatis personae of real and fictional characters comprising the Davidsbündler.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Schumann

Augusta Read Thomas (b.1964 – Glen Cove, NY)

Morse Code Fantasy

Thomas is Professor of Composition in Music and the College at The University of Chicago, and has been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. She is among the most widely performed composers of our time. Her brilliantly playful “Morse Code Fantasy” riffs on Schumann’s penchant for enigma and code, as well as the manic, mercurial alternation of outgoing and introverted characters. Her piece shares motivic DNA with the third dance from Schumann’s set, which it precedes: a rising scale in the rhythm of a polonaise.

https://www.augustareadthomas.com

Martin Bresnick (b. 1946 – Bronx, NY)

Bundists (Robert, György and me)

The beloved composition teacher of several composers on this album, Bresnick has taught at the Yale School of Music since 1981. His numerous awards include the Rome Prize, and his own teachers included the legendary György Ligeti, whose Autumn in Warsaw Etude serves as a point of departure for “Bundists (Robert, György, and me)”. A frame within a frame, this multi-century mashup invites the listener to peer at Schumann’s fourth dance as if suspended within a musical snow globe– a premonition of eery quietude amid a tumultuous and convulsive outer section.

https://www.martinbresnick.com/

Michael Stephen Brown (b. 1987 – Oceanside, NY)

IV. Ungeduldig

Brown is a renowned pianist and one of the most sought after chamber musicians in the US. His compositions have been championed by distinguished ensembles and soloists, and most often by his devoted circle of friends and collaborators– a Michaelsbund in Washington Heights. While Bresnick’s piece preludes and foreshadows Schumann’s fourth dance, Brown’s fragment arrests it in midair, holding it captive while it beats its wings before finally breaking free and alighting once again into flight.

https://www.michaelbrownmusic.com/

Marcos Balter (b. 1974 – Rio de Janeiro, Brazil)

***

Balter, who first came to the United States in his student days, has crafted a unique compositional voice rooted in the strains of European modernism, but diffused in his own alluringly insectile sound-world. He has received numerous awards and commissions from major orchestras, and has been especially associated with members of the International Contemporary Ensemble. He is a professor at Columbia University. Memorably, he hand-delivered the beautifully handwritten manuscript of his piece, a recomposition of the 5th number in Schumann’s cycle, like a secret letter from a friend in another century. Schumann’s original melody is lobbed into a gravity-free harmonic world, where it floats in celestial bliss. The piece has no title, per se, but three stars drawn at the top of the page give a clue — a characteristically Schumannesque enigma borrowed from his “Album for the Young.”

https://marcosbalter.com/

Gabriel Kahane (b. 1981 – Venice Beach, CA)

No. 6 Sehr rasch und in sich hinein

A true musical polymath, Kahane occupies a rare niche as both indie singer-songwriter and chamber music composer. Kahane’s songs frame the issues of contemporary society in a poignant, personal light, while his instrumental writing draws from the well of American music from Muddy Waters to John Adams. Altogether, what blinkered A&R suits might mistake for a split musical personality is in fact an inimitable compositional voice. His piece is superimposed onto Schumman’s score, dipping in and out of the original through jump cuts, fade-outs, and record-skips. The alternating material by Kahane is at once gritty and playful, with a mid-century-modern American sound that reminds one of the fugue from Barber’s Piano Sonata. As if a distant radio frequency keeps interfering with broadcast, occasional fleeting remembrances of another work dedicated to Clara Wieck, the opening motive of Schumann’s A-minor piano concerto, fade in and out.

https://gabrielkahane.tumblr.com/

Timo Andres (b. 1985 – Palo Alto, CA)

Saccades

A Pulitzer finalist, Andres has honed an erudite but lithe compositional voice deeply intertwined with his activity as a pianist, his music often reflecting the influence of the repertoire preoccupying him at the keyboard. He teaches at the New School while dividing a frenetic performing and composing schedule among a varied coterie of collaborators, from Sufjan Stevens to Jonathan Biss. Kahane and Andres, like buddies at the summer camp pool, coordinated their pieces to run continuously into one another — or attacca. The pas de deux share the approach of alternating Schumann’s music with sections of original, contrasting material. In Timo’s case, these sections expand upon the wedge shaped string of chords that opens the Schumann, till ever wilder gestures finally burst the seams. Just as many children have a nickname at home, Andres’ piece actually wore its default filename of “Dave Project” for the last decade. But in advance of this record, he finally gave the piece its proper name, “Saccades,” which captures something of how its gaze darts away from Schumann in bouts of fleeting, agitated distraction.

https://www.andres.com/

Andrew Norman (b. 1979 – Grand Rapids, MI)

Vorspiel

Norman, whose playful and arresting music has won him major international prizes, has served as the Debs Composer’s Chair at Carnegie Hall and teaches at the USC Thornton School. His concertos and orchestral works are played constantly around the US and abroad, as is his Companion Guide to Rome, which is one of the only contemporary string trios to enter the standard repertoire. His music plays inventively with timbre and rhetoric, and he develops his ideas with elegant economy. Norman generously allowed me to suggest the title “Vorspiel”, which means prelude in the grandiose context of German romantic opera. This title seemed a wry overstatement in the case of a piece so minute, as intimate and raw as exposed nerve endings; but it also alludes to the way in which this prelude resists its eventual ellison into Schumann, with a chain of dissonances pulling achingly backward, like Tristan and Isolde’s ambivalent desire for the Liebestod.

http://andrewnormanmusic.com/

Han Lash (b. 1981 – Alfred, NY)

Liebesbrief an Schumann

Now a professor of composition at the Indiana University Jacobs School, Han Lash is an artist of irrepressible creativity: in addition to being a composer of atmospheric and evocative pieces for orchestras, ensembles, and soloists, they are also a performing harpist and dancer. Occasionally combining these different strains, Lash has performed their own concertos for harp in Carnegie Hall and with the Seattle Symphony. Their piece for New Dances, “Liebesbrief,” or love letter, sounds as if it has no bar-lines. It distills the fantastical, dreamy world of Eusebius to its aetherial essence. Its central motive, a delicate and wispy sounding scalar flourish, comes from its wild alter-ego in the Schumann – the twelfth movement, marked “with humor,” which is an uptempo dance over the nineteenth century equivalent of stride piano.

https://www.lashdance.org/the-artist

Michael Gandolfi (b. 1956 – Melrose, MA)

Mirrors and Sidesteps

Gandolfi, who has mentored several of the composers on this album through his longtime involvement with the Tanglewood Music Center, as well as through his post at the New England Conservatory, is an endlessly curious musician as comfortable amid the thorns of modernism as in the anthems of heavy metal. His distinguished career as a composer is defined by extensive, multi-year collaborations, such as his numerous projects with Robert Spano and the Atlanta Symphony. Gandolfi’s scintillating “Mirrors and Sidesteps” reimagines the final movement from the Schumann – by reflecting, refracting, and warping the same set of notes, the original is barely recognizable.

https://michaelgandolfi.com/

Ted Hearne (b. 1982 – Chicago, IL)

Tänze

Hearne, who serves on the faculty of the USC Thornton School, has forged a unique artistic practice as a composer-performer, creating cantata-form works with texts that confront society’s most pressing and polarizing issues, from government surveillance to gentrification. Hearne is a charismatic performer whose music often requires him to sing while conducting, playing a keyboard, manipulating a laptop, and occasionally meandering to the piano. His emotionally charged and dramatic sound-world saturates the listener’s attention with bracing intensity, equally so in his purely instrumental music. In “Tänze,” Hearne asks for percussive sounds created by aggressively damping the strings. By turning the grand piano into a drum machine, he distills the rhythmic element of the opening Schumann mazurka to its most potent and raw matter. Originally intended to open the new cycle with a series of jarring interruptions to the first piece, “Tänze” now acts as a reprise, creating a structural rhyme that helps to sustain the expanded scale of the New Dances.

https://www.tedhearne.com/

Samuel Carl Adams (b. 1985 – San Francisco, CA)

II. Quietly

Adams has earned wide acclaim for music of stealthy emotional power, undergirded by nuanced rhythmic structures and a downright ravishing sense of harmony and sonority. His music has attracted commissions from major orchestras as well such legendary performers as Emanuel Ax and Esa-Pekka Salonen. For New Dances, he chose Schumann’s refrain, appearing twice as the second and also penultimate movements of the cycle. In its repetition, this refrain is both structurally vital and poetically ecstatic. Likewise, Adams wrote two iterations of his beautiful piece: the first appears midway through the cycle, providing a sense of reprise along with Hearne’s “Tänze;” the second melds into its Schumann counterpart near the end, tying the whole structure of the New Dances together. Adam’s music shadows the harmonic plan of the original Schumann, and builds upon its duple against triple polyrhythm: he adds a layer in 5/8 time, so that the transition from his piece back into Schumann slowly peels back layers to reveal a delicately beating heart.

https://www.samuelcarladams.com/

Mark Carlson (b. 1952 – Fort Lewis, WA)

X. Sehr rasch

Carlson recently retired from the UCLA composition faculty, where he was a cherished mentor, and has been a creative force in the Los Angeles music scene for decades. Through dozens of new works for and his long running chamber music series, Pacific Serenades, Carlson has contributed immeasurably to the cultural landscape in California and beyond. His compositional style is lyrical and sophisticated, creating music that is paradoxically unpretentious yet unimpeachably crafted. In his movement for this cycle, he turns the amp “up to 11” on Schumann’s already turbulent emotional world. Unlike Hearne, who interrupts Schumann with a jarringly dissimilar soundworld, Carlson subtly expands Schumann’s harmonic palette and metrical interplay with more tortured chromaticism, wilder pyrotechnics, and more florid tantrums of polyrhythmic activity. As phrases by the two composers weave seamlessly in and out of one another, it can be difficult to discern which music is by Carlson and which is by Schumann.

https://www.markcarlsonmusic.com/

Ryan Francis (b. 1981 – Portland, OR)

Reminiscence

Francis teaches at Pacific University, and has distinguished himself especially as a composer for the piano. His sometimes muscularly virtuosic, sometimes searingly poetic music is always idiomatic for the instrument, making his music a best kept secret of sorts with a generation of dynamic New York pianists that includes Vicky Chow, Han Chen, Elizabeth Roe, and Conor Hanick. For his “Reminiscence,” Francis reflects on one of the most lyrical Eusebius movements, a song without words that layers a wandering chromatic inner voice with a soaring attestation of love between two singers in the upper line, like a couple exchanging vows. The new work borrows the tone and texture of the original (the vibe, as the kids say), but crafts the melody into a direction all its own.

https://www.pacificu.edu/about/directory/people/ryan-francis-dma

Caroline Shaw (b. 1982 – Greenville, NC)

XVI. Mit gutem humor un poco lol ma con serioso vibes

Shaw’s music, which operates with an alchemistic blend of sophistication and simplicity, made her the youngest ever recipient of the Pulitzer Prize in Music. Also a violinist and singer, she performs frequently with her collaborators, from Room full of Teeth to the Attacca Quartet. The mix of sharp wit, play, tenderness, and utter lack of pretension that characterize her music all come across in the performance instruction above, which though nonsensical, requires no explanation. Shaw telescopes into a micro-motive, a fragment from one of the most tired of musical cliches, the circle of fifths sequence, and spins it out till it stretches the edges of the keyboard. Exactly half-way through her perfectly symmetrical miniature, all activity implodes into a humble, beautiful chorale, right as rain.

https://carolineshaw.com/

Caleb Burhans (b. 1980 – Monterey, CA)

Leid mit Mut

Also a composer-performer, Burhans is among the most prolific artists on New York’s dynamic and bustling contemporary music scene, where he plays violin and viola, and occasionally conducts. One of the original founders of Alarm Will Sound, ensemble signal, and the Wordless Music Orchestra, he regularly plays with ACME and on Broadway and television. His compositions, meanwhile, have been sought by the JACK and Kronos Quartets, eighth blackbird, and Room Full of Teeth. His beautiful remix of one of Schumann’s most austere and plaintive movements saps even more sentiment out of its ancient sounding melody. Dipping into the lowest registers of the keyboard, it sounds as if it plumbs the depths of pain and strength, hence its title: “sorrow with courage,” which is borrowed from the epigraph that begins the Davidsbündlertänze.

http://www.calebburhans.com/